Tags

Adam Cohen, American history, biographies, book reviews, FDR, presidential biographies, Presidents

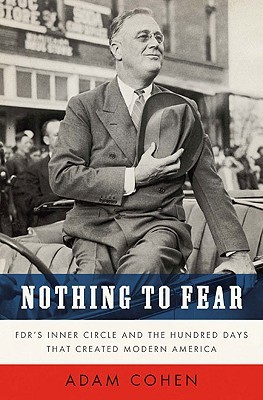

“Nothing to Fear: FDR’s Inner Circle and the 100 Days that Created Modern America” is Adam Cohen’s 2009 review of the early days of the Franklin D. Roosevelt presidency. Cohen is a former lawyer and member of the New York Times editorial board. He is currently an editor at The National Book Review.

“Nothing to Fear: FDR’s Inner Circle and the 100 Days that Created Modern America” is Adam Cohen’s 2009 review of the early days of the Franklin D. Roosevelt presidency. Cohen is a former lawyer and member of the New York Times editorial board. He is currently an editor at The National Book Review.

As its title suggests, “Nothing to Fear” is not a comprehensive biography of Franklin Roosevelt nor is it a thorough examination of his entire New Deal program. Instead, it is a narrative that stitches together a review of FDR’s first “Hundred Days” and mini-biographies of five of his closest advisers.

The 318-page book begins as FDR takes office and Cohen thoughtfully devotes most of the first chapter to setting the economic backdrop against which Roosevelt assumed office. As part of this exercise the author castigates the Hoover administration for its failures, but otherwise very little political bias is evident. Only when two of the book’s final three paragraphs are devoted to lambasting contemporary conservative politics is this spirit of near-neutrality destroyed.

In some ways Cohen’s book resembles a mini “Team of Rivals” but without the same analytical depth or character development which Goodwin injected into her book (covering the Lincoln administration). Nonetheless, this successful journalist’s writing style leads to a narrative which proves remarkably engaging despite the occasionally dry underlying topics.

“Nothing to Fear” provides the reader with a good – but not great – review of FDR’s first “Hundred Days.” Its best feature is the series of biographical sketches it offers of Harry Hopkins, Frances Perkins, Henry Wallace, Lewis Douglas and Raymond Moley – individuals instrumental in driving Roosevelt’s early legislative initiatives but who have been largely (if not quite entirely) forgotten.

Cohen’s narrative occasionally becomes so focused on these men and women at the center of FDR’s progressive program that it loses contact with the Hundred Days altogether, if only for a few pages at a time. And although the reader frequently encounters President Roosevelt himself, his character and personality (as well as his politics to a significant degree) remain mostly unexplored.

Because FDR’s Hundred Days did not end the Depression – or witness all of his notable progressive achievements – the book feels somewhat incomplete when it ends. In an effort to mitigate this, the final chapter briefly covers FDR’s agenda beyond the Hundred Days and follows the primary characters past Roosevelt’s presidency. Still, one gets the sense this book would love to have had its mission expand to cover the entire New Deal.

Overall, “Nothing to Fear” offers an engaging review of the earliest months of FDR’s presidency. Cohen provides a solid, but not exceptional, review of these “Hundred Days” and often excellent biographical vignettes of some of his key advisers. However, this is a book which will best serve readers already familiar with Roosevelt seeking to learn more about his inner circle, not for readers new to FDR intent on reading “just one” book on each U.S. president.

Overall rating: 3¾ stars

How many FDR books do you have left?

17 down, 2 to go!

Is this the most you’ve done on a single president?

I consumed about 9,500 pages of Abraham Lincoln bios; FDR will have provided over 11,000 when I’m done. I’ll be glad to be on to Truman 🙂

I read Nothing to Fear, while I was taking a payroll accounting class. It was random; I was not planning that. It was helpful providing background information to payroll taxes, because a lot of Payroll taxes date back to the 1930s. 🙂

I am a history teacher who really appreciates your blog. Thanks. Info today is like trying to drink from a fire hydrant. Thanks for providing sippy cups!

I really appreciate the nice note – and believe me, there are days when drinking facts out of a sippy cup is about all I can handle!

“The New Deal: A Modern History” by Michael Hiltzik is a good history of the whole New Deal.

I own this 100 Days book and started to read it, but could see that it would be somewhat incomplete and never continued it. It is interesting that it provides a slightly different take on the characters than other accounts of “The Brains Trust.”

I did enjoy your review and learned a few things.